(Bloomberg) — In 2021, a remote mining town in northeastern China has been forced into an unprecedented fiscal consolidation. The ensuing predicament bodes ill for President Xi Jinping, and other heavily indebted municipalities are expected to follow suit.

Bloomberg’s most read articles

Hegang, a city of about one million people near the Russian border, had more than twice as much debt as its financial income when it hit the news about 18 months ago. It is the first time that city authorities have taken official emergency measures since the State Council issued regulations on how local governments from counties to provinces should deal with debt risks in 2016.

Residents of Hegang now feel the brunt of the fiscal tightening. During a recent visit to the city, locals complained of a lack of indoor heating in freezing winter temperatures, and taxi drivers said they were hit with additional traffic fines. Public school teachers feared rumors of layoffs, and street sweepers endured two months behind pay.

Outside the city’s largest hospital, a middle-aged orderly woman in green scrubs and a mask is forced to work on holidays after her employer unilaterally changed her work contract from a government-run medical facility to a third-party vendor. He said that he had cut benefits such as paid overtime for workers. Her monthly salary of 1,600 yuan ($228) has fallen more than 10 days a month since the end of last year.

“I am angry about this situation,” said the woman, who asked to remain anonymous to speak freely about working conditions as she pushed a wheelchair full of flattened cardboard boxes to an outdoor recycling point. “Everything is very expensive. I can barely eat three meals a day.”

Wako is just the tip of the local government debt problem that threatens to make investors increasingly anxious and drag down the world’s second-largest economy for years to come. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimates China’s total government debt is about $23 trillion, which includes hidden borrowings from thousands of financial firms set up by provinces and cities.

Local governments are relatively unlikely to default on their debts in China, given that the Chinese government implicitly guarantees their debts, but the bigger concern is that local governments will be hurting to continue paying their debts. It must either cut spending or redirect funds to growth-enhancing projects. At stake for Mr. Xi is his ambition to double income levels by 2035 while narrowing the gap between rich and poor. key to stability.

“Many cities will look like Hegang in a few years,” said Howes Song, an economist at US think tank Macropolo. He said it meant they didn’t have the labor force to sustain growth and taxes. Earnings.

“By asking banks to roll over local government debt, the central government may be able to maintain stability in the short term,” Song said. “The reality is that more than two-thirds of rural areas will not be able to repay their debts on time,” he added, without loan extensions.

In Heilongjiang province, where Hegang is located, bond investors are already wary of the risks. The state’s seven-year bonds outstanding yielded an average of 3.53%, 18.8 basis points above the national average and among the four most expensive.

Fiscal consolidation can be triggered either when interest payments on municipal bonds exceed 10% of expenditure or when local government leaders deem it necessary. China-based Yuekkai Securities estimates that in 2020, 17 cities will also have bond interest payments exceeding 7% of budget spending, meaning they are approaching the 10% threshold. . These cities are mainly in poor provinces such as Liaoning in the northeast and Inner Mongolia in the north.

Unlike corporate debt restructurings and US local bankruptcies, China’s financial restructuring does not mean that creditors have to lose what they owe.

The problem is evident in other cities as well. Shangqiu, a city of 7.7 million people in central China’s Henan province, made headlines recently when its only bus service was nearly shut down. In Wuhan and Guangzhou, proposals to cut medical benefits for pensioners sparked rare street protests earlier this year. Civil servants in wealthy cities like Shanghai have reportedly had their salaries cut. In Guizhou, officials are begging the Chinese government for help.

For years, the Chinese government has constrained local governments in particular for “hidden” types of debt risk, i.e. debt raised by funding instruments on behalf of local governments but not appearing on local balance sheets. I have asked you to Finance Minister Liu Kun and other officials have tried to allay public concerns by saying local government finances are generally “stable.”

“The local government debt problem is spreading across the country,” said Jean Oi, a political science professor at Stanford University who specializes in China’s fiscal reforms. “Wealthier coastal areas will have more opportunities to repay their debts and access more resources, while less developed areas like Wako will be even more limited in what they can do.”

Decline of Heghan

Wako faced years of coal industry decline and taxpayer losses as the city’s population fell 16% in the decade to 2020. Then came the double blow of the pandemic and the Chinese government’s crackdown on the property market: Xi’s tough coronavirus outbreak, as revenues from land sales, a key source of income for local governments, plummeted. Expensive bills to enforce strict testing and quarantine policies were suddenly faced.

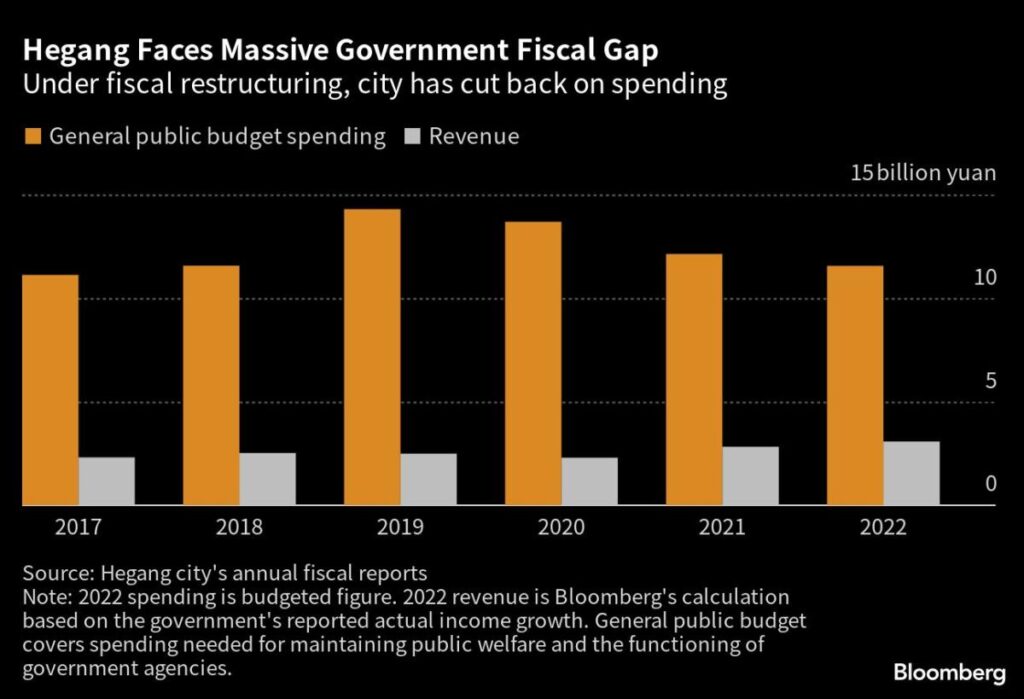

In 2020, Wako announced that it would not be able to pay the interest and principal equivalent of 5.57 billion yuan on debt due to lack of funds. According to official sources and media reports, the city’s total debt, including off-balance sheet debt, will reach nearly 30 billion yuan by 2021, or about 230% of total fiscal revenue.

Wako has made some progress in curbing its debt ratio to 209% by 2022, but the company’s efforts to crawl out of its fiscal hole represent an easy solution for Xi and his economic team. indicates that there is no remedy.

The city’s general revenue, which comes mainly from taxes, is budgeted to grow by 9% in 2022, partly due to rising coal prices, but that may never happen again. Also, fines and income from the sale of state-owned assets were projected to increase him by 10%, but this is only a fraction of what his Hegang needs in his budget. About half of the city’s revenue last year came from remittances from state governments, according to available official data. Wago has not disclosed its budget for 2023.

Local officials are touting new industries such as tourism and graphite mining as revenue streams to reduce the city’s reliance on coal. But graphite—the mineral used in everything from pencils to electric car batteries—is a relatively small industry, accounting for just one-sixth of the city’s coal sector as of 2020. And the authorities have decided that three national forests, a wetland nature reserve, a remote location, and winter temperatures as low as -20 degrees Celsius (-4 degrees Celsius) make it a year-round destination for tourism. As a tourist attraction, it has limited appeal.

In the annual government work report released in March, Hegang Mayor Wang Xingzhu said that “traditional industries are in urgent need of upgrading and transformation”, while “emerging industries are not strongly supporting the economy. ” he admitted. Still, he was optimistic that the city was working to reduce some of its off-balance sheet debt and that “the peak period of debt service has passed smoothly.”

One of the potential attractions for Wagang is low property prices, especially among a generation of ‘liars’ who are disillusioned with the high stress and cost of living in China’s big cities. Hegang has the lowest housing prices of any Chinese city, a side effect of oversupply and population decline.

Diya, 33, a singer and music teacher, wanted to use her stage name, but moved to Hegang from Shanghai two years ago. According to him, it’s the kind of place “even if you do your best and work 24 hours a day.” On that day I will not be able to make enough money to be rich or own a house. ”He can now afford to own three properties in the city. That includes his current home, his third-floor walk-up apartment of 50 square meters for his 40,000 yuan, about 1% of the price of a similarly sized house in Shanghai. is.

“Colleagues, friends and relatives all laughed when they heard I was moving to Hegang because it is considered going to a lower place,” he said. “But Hegang is a place where you don’t need a lot of money or ambitions to live well. It’s like a haven for me.”

The longtime residents of this city are just trying to survive.

Every day, groups of old coal workers in worn-out military hoodies gather on the roadsides of Hegang at dawn. They want a shovel in hand and a day job loading coal onto trucks and trains. One of them, Ms. Zhang, said she could earn 100 yuan (about $15) on a good day. But often she is lucky that she can earn only 10 to 20 yuan for “hard work”.

“We don’t have any subsidies or pensions,” said 66-year-old Chan, who asked for his last name. “I will not retire until I am physically unable to work.”

— Reporting by Colum Murphy and Yujing Liu

–With help from Mr. Jing Zhao.

Bloomberg Businessweek’s Most Read Articles

©2023 Bloomberg LP